Theorizing Hypermodernity and the Politics of Belief (Pt. 1)

12/14/2025

The primary thesis that HPB builds off of is Kristeva’s deconstructive discovery that the core philosophical distinction of subject and object is incomplete without a displaced (and thus destabilizing) third term: the abject. In Kristeva’s terms, the abject can be described as that which must be violently dispelled to form and maintain the subject and which yet remains frighteningly close to the subject, a repressed, segregated aspect of its identity that threatens to tear it apart and must be continually rejected. For instance, examples include bodily fluids (shit, blood, piss, vomit), corpses, venereal diseases, and psychotic madness. As the rejected part of psychosomatic experience, the abject can be understood as the Other living within, even when, like bodily fluids or a cured virus, it has already been expelled by the flesh or mind. In essence, the abject is the repressed excess which fractures and destabilizes any objectifying identity category, that disrupts normativity, that ruptures and breaks the image that claims to be an essence, that is in and of itself the broken image of an essence that can never be fully represented, the denied emptiness in any right to claim the soul of the Other, the emptying capacity of the image and its shackles, that emptiness that speaks in the image, the lack which exudes its own excess, the dark precursor that disestablishes order and leads to either collapse or creation. More simply, as Kristeva says, the abject functions as the ultimate disturbance to “identity, system, order. . .borders, positions, [and] rules.” It is ultimately the autotransgressive force underlying, and thus capable of either destroying or deconstructing, any belief about self, other, or the world.

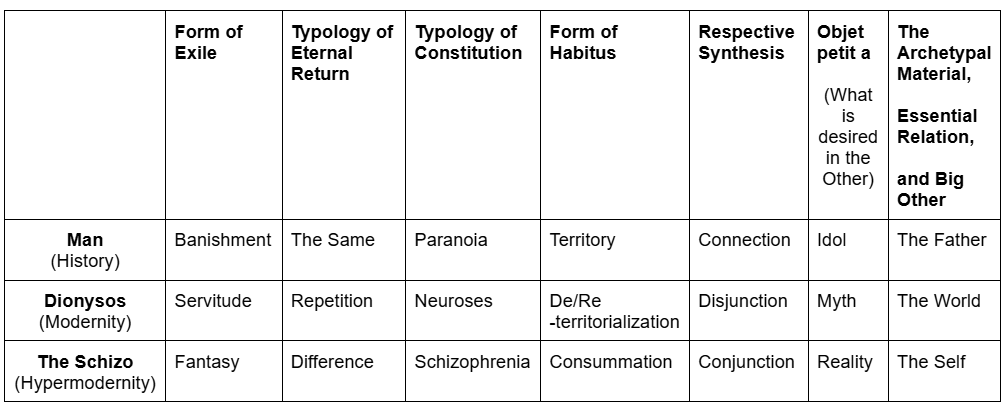

By combining Kristeva’s insights on the abject, powerfully articulated in her 1980 work The Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, with the more post-Lacanian and Nietzscheo-Marxist insights of Deleuze and Guattari in their Capitalism and Schizophrenia series, I work to show how the abject is not merely a psychological phenomenon whose encounter links us to the Real, but can in fact be a productive counter-deterritorializing force allowing us to confront hypermodern capitalist accelerationism. In this case, I examine how the abject functions as a part of transsubjective identity that cannot be objectified, cannot be made into a stable, consistent model image or form for codification, making it outside of the realm of possible commodification. By exploring, surveying, and mining the abject, we participate in a deconstructive and deterritorializing process that I refer to as abjectivity in contradistinction to subjectivity and objectivity. Abjectivity operates somewhere between the subjective and objective, between the self and other, the imaginary and the real, the surreal and infrareal, something that is not fully falsifiable and yet elicits fascination, a kind of horror and a kind of joy that makes us believe in it at the same time that it makes us question the beliefs that allows us to normally function as stable egos in ourselves and in the world. It is this transgressive potential — a potential which may be (cautiously) approached and potentially influenced through psychosomatic investment, but is essentially autonomous — that makes it potentially a radicalizing, transformative, and still yet frighteningly destructive force.

As Nietzsche already noted, a force in the individual or collective psyche always produces a dominant affective response, and the type of affect that emerges in relation to that force determines the general direction, form, and viability of that psychosomatic body in regards to its environment. I argue that there are two underlying affects (and affective economies) that have dominated the human psyche: the oceanic and the apocalyptic. The oceanic, which is considered a mythic case and thus part of the imaginary, is the fantasy of a complex general economy in which the split between self and other is either absent or at least experienced in another way through a porous ego; the other affect, on the other hand, is the apocalyptic reality of the conscious/unconscious/self/other split, the mode of being which allows for discrete identity and thus separation and repression. The first affect, the oceanic, is a myth in the sense that it is a story about pre- and the possibility of post-egoic consciousness (Wilber’s pre and trans fallacy is pertinent here), whereas the apocalyptic affect is the natural refutation of that myth. In other words, the oceanic represents the myth of uninterrupted wholeness (was Man ever truly one with with the (M)other?) and the apocalyptic manifests as the divisionary egoism that splits that wholeness into hierarchical relations (O, how Man excepts himself!). The apocalyptic dismemberment of the body of the oceanic is the process of exaltation and abjection (O, how Marduk tears apart the limbs of Tiamat to craft his world!); the abject is the refuse, the expelled remains of all that is outside the ritual commodities such as idol, essence, archetype, figurehead, and territory. It is these ritual commodities that create the fantasy of the striated universe and thus allow for the conscious mind to participate in the oikos (eco-system, eco-nomy) of capitalist, religious, and social common sense.

Ultimately, the apocalyptic logic of capital is that everything can be de- and re-territorialized into ideological capital, and the excess which escapes capture in the moment can be repressed until shifting faultlines allow/demand further recapture. The notion of the primitive accumulation of belief refers to the ways in which capital has always-already seized control of the possibility of any given future belief before it can emerge. By ordering each thing as an object of utility (idol), value (essence), meaning (archetype), need (figurehead/salesman), and purpose (territory), capitalism separates its own products from any “original” that could exist — the mythic referent, the signifying signified from the untouched past, the presubjective Other that lays the foundation, maintains the origin, and justifies the chain of identity — the simulacra of which proliferate as so many partial objects which may be essentialized by new figureheads and archetypicalized as the new reality. A slow, aberrant deterritorialization in which “essence has been razed” (“They Come in Gold”, Shabazz Palaces) and yet continually haunts the order of things, ala Blake’s “The Ghost of a Flea”. The issue here is not that capitalism extracts the new for profit or control, but rather that its objectifying/commodifying/essentializing habit of representation is selling ourselves back to us before we can truly assess who we are, where we are going, or where we come from — at times wondering if from anywhere at all…

Again, the problem arises not in that capitalism is capturing every last element of our difference and selling it back to us, per se, but that it is extracting our self-extractions and selling them back to us at such a rate that in the face of being sold the same fantasy — that our differences are compartmentalized into clean categories of self and other, ego and group, us and them — the actual traumas of our colliding primordial and accumulated differences are under the pressure of exploding as potential psychopolitical volcanic faultlines. Thus the categories of species, race, gender, ability, religion, and politics are so many essentialized ritual commodities that we trade within the factories of ideological capital in order to separate and congregate, but the splits between each other and within ourselves speak to the underlying fact that these categories are artificial at best, and explosive at worst. At the same time that they allow the possibility of collective referent, they constrict and agitate; again and again, they fall short and spark and spit and shatter from the friction of an invisible force, the repressed abjectivity of infinite difference. To deny the material reality or pragmatic necessity of these categories is not the goal; it is rather to deny their stability, and thus honor their inherent aberrance. The more the accelerationist fantasy pushes us to identify these categories, and thus exchange and compete for our own forms of their interpretation (e.g. will my vision of the essence of trans-ness as existential mutational openness, and the archetype of the organic transsexual, gain traction in the marketplace of ideas, beliefs, and existential intentionality/action?), the more our ritual commodities battle in the arena of apocalyptic affect. This hypermodernization forces the received real to confront the perceived possible.

At the same time, both products are shipped back to us in a convoluted form, an attempt to market the essence of selfhood in the form of competing ideologies of humanism and posthumanism, the common and the elite, the traditional and the futuristic; all of which we wrap ourselves in whatever combination suits are chosen ideological and aesthetic configuration. The present itself becomes an arena in which everything that’s ever been believed and ever could be believed must struggle for supremacy. So how do you greet this apocalypse — aka the desired end of this combat, this agony, that never comes, for good or for ill? With laughter or screams? Joy or sorrow? Affirmation or nihilism? While the battle over essence and antiessentialism wage on, it becomes possible to either withdraw from the project of confrontation or become so obsessed by it that one essentially loses track of the plot. The withdrawal into voyeurism — just enjoying the collision of difference with ideology — is the passive cousin of the terrorist’s hypervigilance. Either way, the danger is that we isolate into the underinvestment of entertainment or the overinvestment of terroristic paranoia. The problem is neither the voyeur nor the terrorist has any future to believe in — only a flooded present and a mythical past. Flooded by images or flooded by immigrants; either way the fantasy continues. Thus capitalism’s ability to sell us what we want fuels both impotence and reaction.

Conclusion: The point now is not to succumb to either form of nihilism, passive (the voyeur) or active (the terrorist), but rather to mine the contradictions that emerge between the received and the perceived, expressing modes of thought from the future that extrapolate the past, history and myth, and transform our relationship to the present; in other words, the job of the schizo is to follow lines of flight into the possible and back again, to immanentize future politics. Futurism, in this sense, is the confrontation with the eerie, weird, surreal, and infrareal space of hauntology, hyperstition, death, fantasy, nonsense, chaos, and the impossible.