This section of IGF serves as an introduction to the history of its author and the space-times, wounds really, that gave rise to its material and conceptual production as a budding larva. The spaces and times selected —the psychward, the closet, the bottle, the coven, and the simulation — were all junctures of what I term to be “schizzing out”, or, in other words, states of deterritorialization toward the outside(s) of consensus reality. They are not meant to appear as idealities; rather, they are points of madness, depression, anxiety, mania, trauma, ecstasy, and crisis that gave rise to the “vision” or “testament” that I hope to articulate in this book. In the following post, I will explore each spatial history briefly.

The Psychward

From 2016 to 2018, I experienced severe manic episodes, to the point of psychosis, each and every Spring. They generally lasted from March to July and resulted in me being involuntarily hospitalized roughly five or six times. During these periods I wrote two books, Trash River Harvest: A Love Story (a novel) and a very rough venture into what would eventually become IGF. I made a commitment to make my madness meaningful during the long depressive months between episodes. In doing so, I’ve chosen to include a section on the psychward as a place for thinking beyond the hegemonic structures of capitalism, colonial and imperial Christian patriarchy, and Western common sense. Each of these forces exists as a means to disenchant the world of the Other and the being of the Earth, and to schizz out out of their boundaries is to encounter hidden worlds, both miraculous and dangerous.

This period saw me living out what I thought was the apocalypse — the end of the world as we know it and the coming of Zion, the Kingdom of God. As I will elaborate further in later sections, I was convinced that I was an alien spirit and that we were all in a simulation or, to put it another way, a God dream. Every person I met was more than a single individual: they were a multitude of posthuman forces clicking away at the ever-awakening Zion-I, the hivemind of God consciousness. I was convinced that the apocalypse, revolution, and (post)human potential were all intimately bound; and at the same time, I was losing my grip on what others considered to be the “real” world. Importantly, I don’t want to romanticize this situation. I was, in many ways, psychotic. However, I also made connections that I believe are significant and worth articulating — particularly the roles that political theology, (re)enchantment, consciousness raising, and decolonial revolution have in relation to one another.

The Closet

08/18/2015 12:18 p.m. During the Apocalypse, you don’t need to leave your closet. Just leave the door open and build a radio station out of garbage.

“71. …And Tonight at the Old Green!: Eulogies”, Trash River Harvest: A Love Story

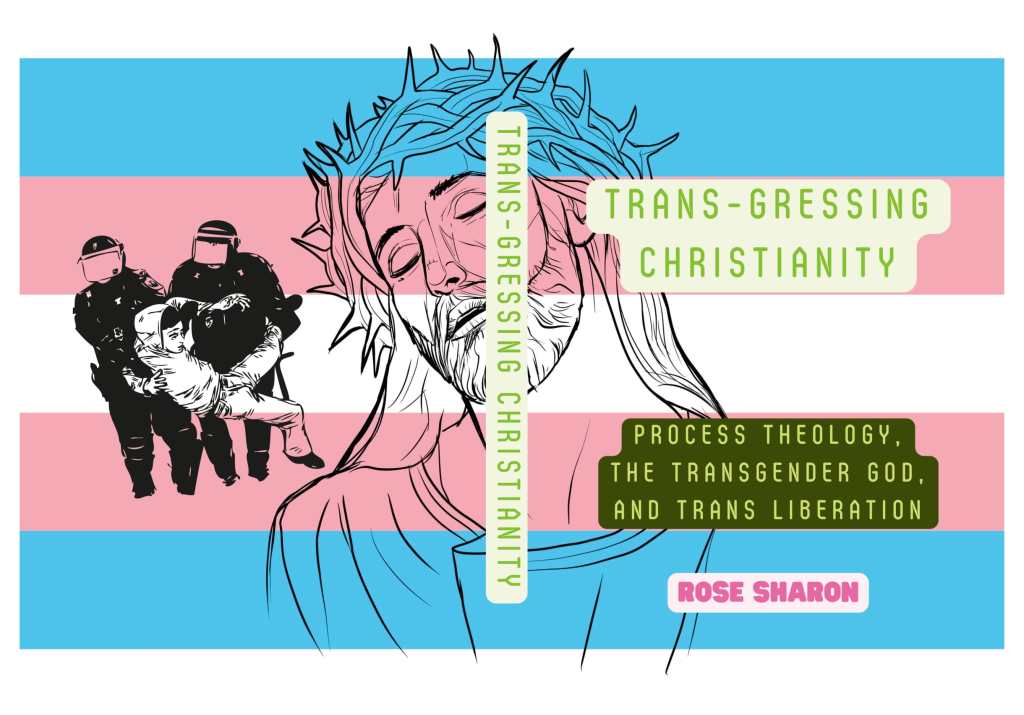

Another significant space in which I’ve worked out my challenges with common sense is my relationship to being in the closet as a queer and trans person. For years, I felt trapped, isolated, dirty, sinful, doomed, perverted, misguided, and maladjusted to the “right” way of living. I was stuck in fear. I couldn’t picture myself acting out my desires without also imagining my eternal damnation. The cisheteropatriarchal God that the status quo had shoved down my throat was always clawing its way through my body, giving foreboding warnings that I would lose my way and end up in Hell if I ever pursued what I really wanted. It was only by letting go of consensus reality that I was able to find a line of flight beyond this hateful, wrathful God. In His place, I found a multitude of divine love, a Mother to all, the harvester of joy, and the consecrator of pleasure. To come out of the closet first required tending to the dark night of the soul within the closet — a path of extreme pain that gave birth to a (re)new(ed) divinity within myself. I found that to know God truly was to truly be oneself, to be one with God was to be the parts of God that even God is afraid of revealing to the world. A queer, trans God; a God that is actually universal because They are the parts of the world that the world most rejects.

This is why I find the figure of Jesus of Nazareth so important. For Christianity to be truly revolutionary, it must, as Jesus suggested, find and embrace “the stone the builders rejected”. As Matthew 21:42 says,

Jesus said to them, “Have you never read in the Scriptures: ‘The stone the builders rejected has become the cornerstone; the Lord has done this, and it is marvelous in our eyes’?”

From my psychotic religiosity, I have come to believe that it is the disenfranchised, the oppressed, the poor, the suffering, and the abandoned which make up this rejected stone. While most scriptural interpretation views this rejected stone as a metaphor for Jesus, I think this misses the true spiritual and political significance of who Jesus was: a mystic who spiritually and politically aligned himself with the oppressed people of the world. In this way, each and every suffering person, as a branch in Jesus’ vine, is one with him in the spirit of God; and thus, each is the foundation stone. To see that Jesus as the Christ is not just an individual person, but is the entire community of struggling humanity, is to discover the Christliness of each and every person. To return to the place of the closet, we must understand that this is a space of deep ministry, mystical union, spiritual trial, and, ultimately, development of the Godhead in its most politically and spiritually realized form.

The Bottle

Throughout the past nine years, I’ve struggled with addiction to multiple substances and have recognized that I’m an alcoholic. In many ways, alcohol has been my means to escape from the drudgery of life in late stage capitalism and the Anthropocene. Watching the world burn around me while constantly being inundated with injunctions to consume things I can’t afford is exhausting, not to mention the pain I struggle with due to my mental health issues, trauma, and the attacks the status quo makes on my identity daily as a queer and trans person. Due to this, the bottle has been my escape, my release, and a space for freedom in difficult hours. Unfortunately, while it does help momentarily, relying on drugs to free oneself often results in a negative feedback look in which drug-induced confidence and spontaneity shrinks into anxiety and anthropophobia when sober. Luckily, however, I am currently nine months sober and finding ways to reacclimate myself to shared existence with my worldly kin.

As a conceptual space, the bottle takes on a performative aspect. Each drink, whether with friends or alone, was a mission, a quest to find happiness or an exaltation of the moment. I would often drink to have the courage to go outside and hangout with travelers and other homeless people in my city, building connections and sharing stories. There were many nights leading up to my first episode when I, still a closeted trans person, would get drunk and put on makeup before strolling downtown and diving headfirst into the bustlings of midnight-drenched city life. I found myself time and time again drinking and listening to music, hearing the words of songs as if they were directly related to me. More times than not, my drinking would coincide with the use of weed or cocaine. I reached heights of experience and synchronicity that I would barely be able to register sober, all before falling into painful, nearly-catatonic slumbers in which whole days would melt away. The bottle was a blackhole taking me into territories of consciousness that existed just below the surface; and, at the end of my explorations, dropping me off in desolation and dismay — the other side of my mania. Alcoholism: the chase of the first drink and the prolonging of the last. As Deleuze and Guattari write in A Thousand Plateaus,

. . .what does an alcoholic call the last glass? The alcoholic makes a subjective evaluation of how much he or she can tolerate. What can be tolerated is precisely the limit at which, as the alcoholic sees it, he or she will be able to start over again (after a rest, a pause …). But beyond that limit there lies a threshold that would cause the alcoholic to change assemblage: it would change either the nature of the drinks or the customary places and hours of the drinking. Or worse yet, the alcoholic would enter a suicidal assemblage, or a medical, hospital assemblage, etc. It is of little importance that the alcoholic may be fooling him- or herself, or makes a very ambiguous use of the theme “I’m going to stop,” the theme of the last one. What counts is the existence of a spontaneous marginal criterion and marginalist evaluation determining the value of the entire series of “glasses.”

A Thousand Plateaus, p. 438

In other words, we drink until we’ve had enough. And, unfortunately for an addict like myself, it’s rare that I’ve ever had enough while using. D&G’s mention of suicidal and hospital assemblages are very personal to my experience as a user, as I’ve sent myself into deep pits of suicidal ideation and, as mentioned previously, been hospitalized many times due to psychosis. However, I do not regret using. I’ve encountered parts of myself — some I like, some I despise, many that I was either truly relieved or fundamentally surprised to meet — that may have remained dormant otherwise. As D&G write again,

To succeed in getting drunk, but on pure water (Henry Miller). To succeed in getting high, but by abstention, “to take and abstain, especially abstain,” I am a drinker of water (Michaux). To reach the point where “to get high or not to get high” is no longer the question, but rather whether drugs have sufficiently changed the general conditions of space and time perception so that nonusers can succeed in passing through the holes in the world and following the lines of flight at the very place where means other than drugs become necessary. Drugs do not guarantee immanence; rather, the immanence of drugs allows one to forgo them. Is it cowardice or exploitation to wait until others have taken the risks? No, it is joining an undertaking in the middle, while changing the means.

A Thousand Plateaus, p. 286

It is my goal, then, to elaborate what I have encountered with drugs so that others may take less destructive paths and, hopefully, develop more constructive futures for themselves and our shared worlds.

The Coven

I have always been drawn to the forest and to the night and the moon. Crises in my spirituality led me away from traditional Christianity toward more heterodox beliefs, such as the sanctity of nature, the feminine aspect of the divine, and the shamanic relationship all beings have to one another. I came to the practice of witchcraft by dabbling in tarot, astrology, esotericism, mysticism, psychedelics, animism, occultism, and what I might call an insurrectionist spirituality.

My politics have always been what guides my theological convictions first and foremost. Before I thought of myself as queer and trans, I began to experience the death of God not just as the secularization of society, but as a profound lack of spiritual ground for my own being. Cycles of depression, suicidal ideation, and nihilism ensued. I felt myself to be a cis straight man living a meaningless life, at least outside of my belief in political revolution. For the most part at that time, I had written off witchcraft and its associated practices as New Age self-help fluff. It wasn’t until I encountered the work of Silvia Federici, author of Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, that I began to understand the history of witchcraft in a materialist, historical, and revolutionary way. That the massacre of and violence against witches in late medieval and early modern Europe was the basis for the jumpstart of capitalism was mind-blowing. That patriarchy was at the heart of capitalism was a humbling realization for me, a queer trans woman-in-denial.

As you’ll see below, I became much more interested in witchcraft’s history and possibilities when I realized I was trans, which was one of the guiding influences for writing my novel, Trash River Harvest. I believe this is most evident in this quote, in which a character called “She” —perhaps a prefiguration of myself as a witchy trans woman — burst out of my inner being and gained control of my body:

I don’t know when it ended, but it was over: she went mad and took control all at once. Before I could catch hold she was running toward the forest with blood in her lungs and screaming at the moon on fire and cracking open streetlamps with nine clawing palms, casting sorceries at prison guards running after her and drinking up the stars with a snaking tongue. She made me feel her pussy as we ran, climb deep inside ourself with bony limbs and spill juices across the dirt that raised up phantoms who evaporated the jailers and the dogs. I was so terrified seeing what she had done and wanted to yell but instead of sound it was only smoke coming out and she battled my flailing mind by driving our fist deeper inside until I was too overstimulated to think or resist or even care that I had lost control of her. She kept pushing farther and farther inside and climbing through brush, always moving past what I imagined to be a natural limit on feeling. I sort of broke away then and became nothing but our fist, a fetus climbing back into my own motherly den and cooing out soft sounds of rest. Perhaps I was just a little wave in an ocean she had conjured up… a deluge that was wiping away mother and father, boy and girl, I and you. She carried me up the mountains on the back of a grizzly, through the springs and summers, falls and winters, ten-thousand years just to lay my corpse in a pit of earth. The beast sprouted from the soil and shook, carried off by a swarm of alien lights to their true self: a burning book?

But it was just a vision discovered running in the woods. When she found an appropriate place to nest – a cave made of rotting logs and underbrush – she laid my body down. The winds of fear howled outside as she covered me in our own blood, speaking in tongues to call demonic spirits into her sanctuary. I felt near to Isaac, at peace with my trust in her gods. She was a witch and I here initiate; we are coven. She was lord and I was her throne; we are cult. She was power and I was a perfect outlet; we are God.

When I woke up again, we were already near the top of the mountain in appearances. There were more rocks than trees and the Sun was beating down on us, melting snow into a million little streams. She had me wrapped onto her back like a babe. Before long, sick as we were, she breast fed me: the sustenance I needed to make it up the winding road of switch backs, black rap swerving in the distant cities – an aquarium of bright lit algae. A beetle – no, a cockroach – walked beside us. Finally, sweating with the spirits, we reached the top called High Noon. I could hear Jeremiah whispering, “I told you,” letters and numbers flying out of his head and into mine.

A sword trapped in a rock at the top, she knew she was unstoppable and removed it, pointing at the Sun – King Arthur and Joan of Arc wrapped in one. The boulder left over she hurled upward and it never fell again; until I, left alone sleeping at the top, was crushed by it in the twilight hours: a seed for the freak tree foretold by travelers and mythmakers alike.

And so I was planted, ready to grow into a far out whiskey fueled tortoise along the Great River atop Blue Mountain…

“53. Apocalypse”, Trash River Harvest: A Love Story

Since writing these words, I’ve committed much more deeply to my practice as a witch. I created a feminist coven with my coworkers right before the pandemic began, in which we shared spiritual insights and held space for one another. This sense of community was one in which I could test out my feelings and experiment with the sacred nature of the Earth Mother, our holy Goddess. Additionally, I recently took a class on Wicca with Phyllis Curott, famed lawyer and Wiccan priestess. What I have learned and will carry with me in writing this book is a focus on the revolutionary nature of the divine feminine and the radicality of feminist consciousness raising as spiritual and political practice.

The Simulation

Finally, we reach the threshold of any spiritual deterritorialization: the idea that our world, in some grand capacity, is a simulation. Importantly, this belief has much in common with world-denying Gnosticism, which suggested that our material world was an illusion created by a fallible, damaged, and potentially-evil god named Yaldabaoth. The simulation hypothesis is in many ways just this idea, but wrapped in 21st century technological language. The most famous promulgation of the simulation hypothesis is the incredibly popular Matrix trilogy.

The simulation hypothesis for me has almost always been somewhat of a non-issue. As I determined as a college freshman, what matters if we or the world aren’t real when we are in fact experiencing ourselves and the world daily? Illusion or not, we have experience and we share a reality.

However, this Cartesian hold soon faded when I found myself in places like the psychward, the closet, the bottle, and the coven. I became convinced that the world we experience every day was not the fullness of reality. Consensus reality was, in many ways, the product of a bastard god. But in my eyes, it wasn’t Yaldabaoth who we had to blame, but rather ‘Man’ — the secularizing Westerner at the heart of the Anthropocene who has gone about disenchanting the Earth, siphoning resources, enslaving and decimating peoples, and destroying the ecological systems that hold our shared webs of life together. In view of this, as I lost my mind I began to imagine that humanity was a project being developed by aliens, angels, spirits, or the Earth Herself, with our ultimate destiny being to overcome ‘Man’ and heal the world. As the Jewish Kabbalistic tradition teaches, we are called to the duty of tikkun olam, or the repairing of the world on behalf of the Godhead.

Thus I imagined the birth of a planetary, hivemind consciousness which would lead us beyond the Anthropocene toward what I articulated as Zion. It is important to note that this is not related to the settler-colonialism of Zionism practiced by Israel, but instead the spirit of (re)turning to our sacred homeland of earthly abundance. Zion is, in many ways, the revolutionary hope of an abandoned people. Through its power of enchantment, we are all called to heal the world, to fight against ‘Man’, and to spread awakened consciousness back to the people.

So what does this have to do with the simulation? It is the idea that at its core, the Earth and the Universe (and potentially their inhabitants) are on the side of justice. This belief in shared higher powers is one that I believe can result in a radical rearticulation of not only who and what God is, but what it means to be human in a posthuman world. In effect, it is a theoretical springboard for imagining a future without patriarchy, colonialism, white supremacy, anthropocentrism, and capitalism. Whether we, God, or the world exists doesn’t matter; but what we imagine, in our rawest madness and sweetest desires, does. So with that, I say this: the simulation is a hypothesis that can be carried or buried. For me, however, it is at the heart of my studies in planetary consciousness and posthuman political theology.

At last, I just want to say that if you read through these musings on my introductory sections, I’d love to hear what you think. Feel free to reach me by email if you have any suggestions or questions. Looking forward to further posts!